- Home

- Mary Higgins Clark

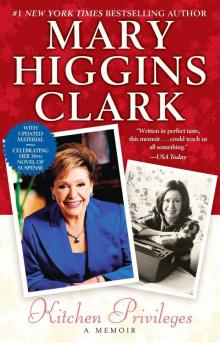

Kitchen Privileges Page 16

Kitchen Privileges Read online

Page 16

The paperback of Where Are the Children? came out in June 1976. Dave was graduating from Dartmouth, and we were all heading there for the weekend. A few days before we were scheduled to leave, I got together with writer Lisa Kent, a longtime friend. Lisa suggested that we have dinner in a little restaurant near the Fifty-ninth Street bridge. “They have someone there who reads palms,” Lisa said. “I hear she’s fabulous.”

I put about as much faith in palmists as I do in reading the astrology column in the newspaper, but I went along with the idea. And, truth be told, I had received one startlingly accurate reading during my Pan Am days. In that instance I’d been walking with some of the crew in New Delhi when a Sikh approached me and asked to tell my fortune.

What he predicted became a family joke: “You are going to marry a baldheaded man at Christmastime.”

Warren certainly wasn’t bald, but he did have a high forehead. I couldn’t wait to tell him about the prediction when I got home.

But then the Sikh had added, “You were seeing a man with a mustache. He is very sad that you are betrothed.”

I had just received a letter from Jack Kean—“a man with a mustache”—saying he would like to get together, and he urged me to dispense with my engagement. Apparently he and girlfriend number one were kaput—again.

I had told Warren about the letter, and he’d said, “Call this joker up and tell him to get lost.” Instead, by my silence, I chose to establish myself firmly as the one who laughs last.

But no question, the Sikh had been on target. I wondered if this new palm reader would come up with anything that even resembled a reasonable prediction.

She read Lisa’s palm first. When Lisa came back to the table she seemed impressed. “She’s pretty good, Mary.”

I went over to her corner. She examined my palms and shook her head. “I don’t believe what I am seeing,” she told me. “You are going to be world-famous. You are going to make a great deal of money. You will live to be very old, and you will die abroad.”

What is this poor soul smoking? I wondered.

The next week, we were up at Dartmouth and wandered into town. The main street there is practically part of the campus, and on it is the Dartmouth Book Store, the oldest bookstore in the country continuously run by the same family. We were browsing through the aisles when Carol grabbed my arm. “Mom, look!”

An enlargement of the advance New York Times paperback bestseller list was tacked to the wall. On it was Where Are the Children? in the number ten spot.

We floated down the block to the Hanover Inn and ordered champagne.

Maybe that palm reader did know her business.

Epilogue

The really big break came a year later. I had turned in the manuscript I called Crossroads, which was published under the title A Stranger Is Watching.

Along the way I had been giving chapters to Pat Myrer, and under her guidance, the story was as good as I could make it. Simon and Schuster had an option on it, and I was keeping my fingers crossed that the editors would be happy with what I had done and would want to buy it. It seemed to me that I kept reading about people whose first book had done well but whose second had been a dismal flop.

Then, too, there was the old adage that everybody has one story in her or him. Maybe I’d shot my bolt. These were the thoughts that kept running through my mind as I sat at my desk in the Aerial office and wrote scripts for one of our new series.

In April 1977, as I was about to leave for class at Fordham, Pat Myrer phoned. “Are you sitting down?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“Get a pencil and write down these figures.”

I listened in a daze. Simon and Schuster was offering five hundred thousand dollars for the hardcover rights to the new book; Dell was offering one million dollars for the paperback.

“Think it over,” Pat said.

“Think it over!” I shrieked. “Call back and say yes before they change their minds!”

I had three classes at Fordham that evening. I didn’t hear one word they said in any of them. I kept writing “one million dollars, one million dollars,” over and over again. Then I wrote it again in roman numerals, over and over. I wrote it up and down the page, across the page.

Between classes I called the kids. “Let’s plan a trip to Europe,” I told them.

My car had one hundred and forty-six thousand miles on it. For weeks I’d been nursing it along, my fingers crossed that it wouldn’t break down. With all the tuition payments, there was no way I could think about replacing it.

Floating on air, I left Fordham that glorious evening and got into the car. As I drove onto the Henry Hudson Parkway, the tailpipe and muffler came loose and began dragging on the ground. For the next twenty-one miles, I kur-plunk, kurplunked, all the way home. People in other cars kept honking and beeping, obviously sure that I was either too stupid or too deaf to hear the racket.

The next day I bought a Cadillac!

The years since then are many, although they seem few. Financially independent, all of the children out of the house, I remarried in 1978. It was a mistake and lasted just a few years.

The night I received my degree from Fordham, I threw myself a prom. The invitation read: “After lo these many years, Mary Higgins Clark is about to graduate from college. This invitation is twenty-five years overdue. Help prove it’s not too late by coming to the prom.” The guests were urged to dress as they had dressed for their high school proms. Suggestions: spaghetti straps; a tulle dress; long white gloves; bright red lipstick; feather cuts; borrow the keys to Dad’s car.

One of our friends in town had always regretted that he had not driven to his prom in the car he coveted as a kid. In the spirit of my prom, he managed to find that same car and bought it, a 1949 DeSoto. Another friend, mystery writer Ed Hoch, had the evening already committed. He wrote: “Dear Mary, I’m sorry I can’t be with you, but in honor of the occasion, at ten o’clock, Pat and I will get in the backseat of the car and neck.”

The younger generation raided the attics to find vintage clothing.

There were weddings and grandchildren. Elizabeth was the first grandchild. At the hospital, a nurse told us she was the baby next to the door of the nursery. In awe, we stood at the window and gushed and cried and pointed out how much she resembled this one and that one in the family. The same nurse came over to us. “Your baby is on the other side of the door.” We looked, and there she was. If they’d asked me to pick her out among all the babies in the nursery, I could have done it. She was the image of the five babies I had birthed.

After Elizabeth, along came Andrew, and Courtney, and David, and Justin, and Jerry.

When I had five children, a husband, and mother under the same roof, I didn’t know I had a small house. When I was living alone, I decided I needed more room. The move to Saddle River, another town in New Jersey, was a happy one. It’s a great gathering spot for all of us. The grandchildren can have pool and tennis parties with their friends. I love to look out the window from my study and see them having fun there.

I have my pied-à-terre in Manhattan, overlooking Central Park. On a winter night, I stand on the terrace and imagine so many years ago, my mother, age nineteen, dancing barefoot in the snow.

I had decided that it wasn’t for me in this lifetime to ever again experience the wonderful relationship that I knew could exist between a man and a woman. Then in early March 1996, Patty called me from the Mercantile Exchange where she works. “Have I got a hunk for you,” she exclaimed. “His name is John Conheeney. He’s been a widower for two years. He lives in Ridgewood.” Ridgewood is one of the towns that border Saddle River.

“He was chairman and CEO of Merrill Lynch Futures. He retired two years ago. He’s handsome. Everybody thinks the world of him. He’s not going around with anybody—I checked. He’s told me he’s read some of your books. Invite him to the party. I think he’d come.”

She was referring to a party I was having on St. Patric

k’s Day, to celebrate the publication of my then latest novel, Moonlight Becomes You.

I invited John Conheeney. He came. He was everything Patty had promised, and more. Eight months later, we were married at my parish church, St. Gabriel’s. My five children and six grandchildren and his four children and seven grandchildren filled the front pews. Now, between us, we have sixteen grandchildren. Happily, they all live near us.

There’s a wonderful old saying, “If you want to be happy for a year, win the lottery. If you want to be happy for life, love what you do.”

I love being a storyteller.

Another definition of happiness is “Something to have, someone to love, and something to hope for.”

All my life, these essentials of happiness have been granted to me in abundance, and for that I am deeply grateful.

With John on our wedding day—November 30, 1996 (CHRISTOPHER LITTLE/CORBIS OUTLINE)

With my wonderful children, Warren, Marilyn, Patty, Carol, and David (CHRISTOPHER LITTLE/CORBIS OUTLINE)

Clark, Mary Higgins 03 - The Cradle Will Fall

Clark, Mary Higgins 03 - The Cradle Will Fall Moonlight Becomes You

Moonlight Becomes You No Place Like Home

No Place Like Home I've Got My Eyes on You

I've Got My Eyes on You I've Got You Under My Skin

I've Got You Under My Skin The Lottery Winner

The Lottery Winner As Time Goes By

As Time Goes By Nighttime Is My Time

Nighttime Is My Time Where Are the Children?

Where Are the Children? The Lost Years

The Lost Years Two Little Girls in Blue

Two Little Girls in Blue Mount Vernon Love Story: A Novel of George and Martha Washington

Mount Vernon Love Story: A Novel of George and Martha Washington All by Myself, Alone

All by Myself, Alone The Melody Lingers On

The Melody Lingers On Just Take My Heart

Just Take My Heart The Second Time Around

The Second Time Around A Cry in the Night

A Cry in the Night Deck the Halls

Deck the Halls We'll Meet Again

We'll Meet Again Before I Say Goodbye

Before I Say Goodbye Piece of My Heart

Piece of My Heart My Gal Sunday

My Gal Sunday Weep No More, My Lady

Weep No More, My Lady Daddy's Little Girl

Daddy's Little Girl The Cradle Will Fall

The Cradle Will Fall Manhattan Mayhem: New Crime Stories From Mystery Writers of America

Manhattan Mayhem: New Crime Stories From Mystery Writers of America Where Are You Now?

Where Are You Now? Loves Music, Loves to Dance

Loves Music, Loves to Dance While My Pretty One Sleeps

While My Pretty One Sleeps Pretend You Don't See Her

Pretend You Don't See Her I'll Be Seeing You

I'll Be Seeing You Let Me Call You Sweetheart

Let Me Call You Sweetheart Remember Me

Remember Me Silent Night

Silent Night Kitchen Privileges

Kitchen Privileges All Around the Town

All Around the Town Death Wears a Beauty Mask and Other Stories

Death Wears a Beauty Mask and Other Stories I'll Walk Alone

I'll Walk Alone The Shadow of Your Smile

The Shadow of Your Smile Kiss the Girls and Make Them Cry

Kiss the Girls and Make Them Cry Manhattan Mayhem

Manhattan Mayhem Deck the Halls (Holiday Classics)

Deck the Halls (Holiday Classics) The Cinderella Murder

The Cinderella Murder All Dressed in White

All Dressed in White You Don't Own Me

You Don't Own Me The Christmas Thief

The Christmas Thief Before I Say Good-Bye

Before I Say Good-Bye Dashing Through the Snow

Dashing Through the Snow The Sleeping Beauty Killer

The Sleeping Beauty Killer Mount Vernon Love Story

Mount Vernon Love Story Santa Cruise

Santa Cruise I 've Heard That Song Before

I 've Heard That Song Before