- Home

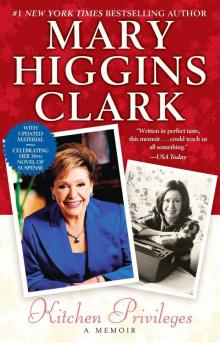

- Mary Higgins Clark

Kitchen Privileges

Kitchen Privileges Read online

By Mary Higgins Clark

Kitchen Privileges

Silent Night/All Through the Night

Mount Vernon Love Story

Daddy’s Little Girl

On the Street Where You Live

Before You Say Good-bye

We’ll Meet Again

All Through the Night

You Belong to Me

Pretend You Don’t See Her

My Gal Sunday

Moonlight Becomes You

Silent Night

Let Me Call You Sweetheart

The Lottery Winner

Remember Me

I’ll Be Seeing You

All Around the Town

Loves Music, Loves to Dance

The Anastasia Syndrome and Other Stories

While My Pretty One Sleeps

Weep No More, My Lady

Stillwatch

A Cry in the Night

The Cradle Will Fall

A Stranger Is Watching

Where Are the Children?

BY MARY HIGGINS CLARK AND CAROL HIGGINS CLARK

He Sees You When You’re Sleeping

Deck the Halls

SIMON & SCHUSTER

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 2002 by Mary Higgins Clark

All rights reserved,

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form.

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Designed by Jan Pisciotta

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7432-0633-4

ISBN-10: 0-7432-0633-9

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

Acknowledgments

Creating fictional characters is a never-ending challenge but in many ways it is easier than telling the story of my own life. Once again I’m truly grateful to my editor, Michael Korda, and his associate, senior editor Chuck Adams, for the daily guidance, encouragement, and support they offered. Again, and always, one hundred thousand thanks. It’s a privilege to work with you.

Eugene Winick and Sam Pinkus, my literary agents, are great in every way. It’s always a joy to work with you.

Many thanks to Lisl Cade, a dear friend and marvelous publicist.

Associate Director of Copyediting Gypsy da Silva continues to be eagle-eyed, unflappable, and wise. Love you, Gypsy.

A tip of the hat to my assistants, Agnes Newton and Nadine Petry. Blessings and kudos to my readers-in-progress, my daughter Carol Higgins Clark and my sister-in-law Irene Clark.

Thank you to all my family and friends who helped me to remember the days gone by.

My love and gratitude to my husband, John Conheeney, our children, and grandchildren. They are my Alpha and Omega.

The tale is told—

This writer rejoices.

For my family and friends

Those who live on in my memory

and

Those who still share my life

With love

The Bronx—me at age four.

Prologue

In the autumn when the trees become streaked with red and gold and the evenings take on the warning chill that winter is coming, I experience a familiar dream. I am walking alone through the old neighborhood. It is early autumn there as well, and the trees are heavily laden with the russet leaves they will soon relinquish. There is no one else around, but I experience no sense of loneliness. Lights begin to shine from behind curtained windows, the brick-and-stucco semidetached houses are tranquil, and I am aware of how dearly I love this Pelham Parkway section of the Bronx.

I walk past the winding fields and meadows where my brothers and I used to go sleighriding: Joe, the older, setting the pace on his Flexible Flyer, little Johnny clinging to my back as we followed Joe’s sled through the twists and turns of the steep sloping field we dubbed Suicide Hill. Jacoby Hospital and the Albert Einstein Medical Center cover those acres now, but in my dream they do not yet exist.

I walk slowly from the field down Pinchot Place to Narragansett Avenue and pause in front of the house where the Clark family lives. Once again I am sixteen and hoping the door will open and I may just happen to run into Warren Clark, the twenty-five year old whom I secretly adore. But in my dream I know that five years more must pass before we have that first date. Smiling, I hurry along the next block to Tenbroeck Avenue and open the door of my own home.

The clan is around the table, my parents and brothers, aunts and uncles, cousins and courtesy cousins, the close neighbors and friends who have become extended family. There’s a kettle whistling, a cozy waiting to keep the teapot warm, and everyone is smiling, glad to be together.

Unseen, I take my place among them as the latest happenings are discussed, the old stories retold. Sometimes there are bursts of laughter, other moments eyes brighten with unshed tears at the memory of this one or that one who had such a terrible time, “never a day’s luck in his life.” Memories come flooding back as I hear the stories retold of tender love matches, of bad bargains made at the altar and endured for a lifetime, of family tragedies and triumphs.

I can speak for no other author. We are indeed all islands, repositories of our own memory and experience, nature and nurture. But I do know that whatever writing success I have enjoyed is keyed, like a kite is to string, and string to hand, to the fact that my genes and sense of self, spirit, and intellect have been formed and identified by my Emerald Isle ancestry.

Yeats wrote that the Irish have an abiding sense of tragedy that sustains them through temporary periods of joy. I think that the mix is a little more balanced. During troubled times, they are sure that it will all work out in the end. When the sun is shining, the Irish keep their fingers crossed. Too good to be true, they remind each other. Something’s bound to give.

Kate. Wasn’t it a damn shame about her? The prettiest thing who ever walked in shoe leather, and she chose that one. And to think that she could have had Dan O’Neill. He put himself through law school at night and became a judge. He never married. For him it was always Kate.

Anna Curley. She died in the flu epidemic of 1917, a week before she and Jimmy were to be married. Remember how the poor fellow had saved every nickel and had had the apartment furnished and ready for her? She was buried in her wedding dress, and the day of the funeral, Jimmy swore he’d never draw another sober breath. And wasn’t he a man of his word?

The faces begin to fade, and I awaken. It is the present, but the memories are still vivid. All of them. From the beginning.

May I share them with you?

My Parents, Nora and Luke Higgins, at Rockaway Beach, circa 1923

One

My first conscious memory is of being three years old and looking down at my new baby brother with a mixture of curiosity and distress. His crib had not been delivered on time, and he was sleeping in my doll carriage, thereby displacing my favorite doll, who was ready for her nap.

Luke and Nora, my mother and father, had kept company for seven years, a typical Irish courtship. He was forty-two and she pushing forty when they finally tied the knot. They had Joseph within the year; me, Mary, nineteen months later; and Mother celebrated her forty-fifth birthday by giving birth to Johnny. The story is that when the doctor went into her room, saw the newborn in her arms and the rosary entwined in her fingers, he observed, “I assume this one is Jesus.”

Since we weren’t Hispanic, in which culture Jesus is a common name, John, the first cousin of the Holy Family, was the closest Mother could get. Later when we were all in St. Fran

cis Xavier School and instructed to write J.M.J., which stood for Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, on the top of our test papers, I thought it was a tribute to Joe and me and Johnny.

The year 1931, when Johnny made his appearance, was a good one in our modest world. My father’s Irish pub was flourishing. In anticipation of the new arrival, my parents had purchased a home in the Pelham Parkway section of the Bronx. At that time more rural than suburban, it was only two streets away from Angelina’s farm. Angelina, a wizened elderly lady, would show up every afternoon on the street outside our house, pushing a cart with fresh fruit and vegetables.

“God blessa your momma, your poppa, tella them I gotta lotsa nicea stringabeans today,” she would say.

Our house, 1913 Tenbroeck Avenue, was a semidetached six-room brick-and-stucco structure with a second half bath in a particularly chilly section of the basement. My mother’s joy in having her own home was only slightly lessened by the fact that she and my father had paid ten thousand five for it, while Anne and Charlie Potters, who bought the other side, had only paid ten thousand dollars for the identical space.

“It’s because your father has his own business, and we were driving an expensive new car,” she lamented.

But the expensive new car, a Nash, had sprung an oil leak as they drove it out of the showroom. “It was the beginning of our luck going sour,” she would later reminisce.

The Depression had set in with grim reality. I remember as a small child regularly watching Mother answering the door to find a man standing there, his clothes clean but frayed, his manner courteous. He was looking for work, any kind of work. Did anything need repairing or painting? And if not, could we possibly help him out with a cup of coffee, and maybe something to eat.

Mother never turned away anyone. She left a card table in the foyer and would willingly fix a meal for the unexpected guest. Juice, coffee, a soft-boiled egg and toast in the morning, sandwiches and tea for lunch. I don’t remember anyone ringing the bell after midafternoon. By then, God help them, they were probably on their way home, if they had a home to go to, with the disheartening news that there was no work to be had.

I loved our house and our neighborhood. Mine was the little room, its window over the front door. I would wake in the morning to the clipclop of the horses pulling the milk and bread wagons. Borden’s milk. Dugan’s bread and cake. Sights that have passed into oblivion as surely as the patient horses and creaking wagons that teased me awake and comforted me with their familiarity all those years ago. A box was in permanent residence on the front steps of our house to hold the milk bottles. In the winter, I used to gauge the temperature by checking to see if the cream at the top of the bottles had frozen, forcing the cardboard lids to rise.

During the summer, in midafternoon, we’d all be alert for the sound of jingling bells that meant that Eddie, the Good Humor Man, was wheeling his heavy bicycle around the corner. Looking back, I realize he couldn’t have been more than in his early thirties. With a genuine smile and the patience of Job, he waited while the kids gathered around him, agonizing over their choice of flavor.

All of us had the same routine: a nickle on weekdays for a Dixie cup; a dime on Sunday for a Good Humor on a stick. That was the hardest day for making up my mind. I loved burnt almond over vanilla ice cream. On the other hand, I also loved chocolate over chocolate.

Once the choice had been made, the trick for Joe and John and me was to see who could make the ice cream last the longest so that the other guys’ tongues would be hanging out as they watched the winner enjoy those final licks. The problem was that on hot Sundays the ice cream melted faster, and it wasn’t unusual for the one who made it last the longest to see half the Good Humor slide off the stick and land on the ground. Then the howls of anguish from the afflicted delighted the other two, who now had the satisfaction of chanting, “Ha, ha. Thought you were so smart.”

Eddy the Good Humor man had lost the thumb and index finger of his left hand up to the knuckle. He explained that there had been something wrong with the spring of the heavy refrigerator lid, and it had smashed down on those fingers. “But it was a good accident,” he explained. “The company gave me forty-two dollars, and I was able to buy a winter coat for my wife. She really needed one.”

The Depression didn’t really hit our family until I was in the third or fourth grade. We had a cleaning woman, German Mary, whom we called “Lally” because she would come up the block singing, “Lalalalaaaaa.” Years later, she became the model for Lally in my second book, A Stranger Is Watching. Back then, she was the first perk to go.

We always had two copies of the Times delivered each day. One copy was saved, and I delivered it to the convent on my way to school the next morning. In those days the nuns were not allowed to read the current day’s paper. But as times got increasingly tough, they were out of luck. Mother had to cancel the delivery of both papers. I guess when you think about it, the delivery guy was out of luck, too.

I wrote my first poem when I was six. I still have it because Mother saved everything I wrote. She also insisted that I recite everything I wrote for the benefit of anyone who happened to be visiting. Since she had four sisters and many cousins, all of whom visited frequently, I am sure there must have been regular if silent groans when she would announce, “Mary has written a lovely new poem today. She has promised to recite it for us. Mary, stand on the landing and recite your lovely new poem.”

When I was finished thrilling everyone with my latest gem, my mother led the applause. “Mary is very gifted,” she would announce. “Mary is going to be a successful writer when she grows up.”

Looking back, I am sure that the captive audience was ready to strangle me, but I am intensely grateful for that early vote of absolute confidence I received. When I started sending out short stories and getting them back by return mail, I never got discouraged. Mother’s voice always rang in my subconscious. Someday I was going to be a successful writer. I was going to make it.

That’s why, if I may, I’d like to direct a few words to parents and teachers: When a child comes to you wanting to share something he or she has written or sketched, be generous with your praise. If it’s a written piece, don’t talk about the spelling or the penmanship; look for the creativity and applaud it. The flame of inspiration needs to be encouraged. Put a glass around that small candle and protect it from discouragement or ridicule.

I also started writing skits, which I bullied Joe and John into performing with me. I served as writer, director, producer, and star. I remember Johnny’s plaintive request, “Can’t I ever be the star?”

“No, I wrote it,” I explained. “When you write it, you get to be the star.”

Mother’s unmarried sisters, May and Agnes, were our most frequent visitors and therefore the longest suffering witnesses to my developing talent. May was eleven months older than Mother and, like her, had been a buyer in a Fifth Avenue department store. Ag, the second youngest in the family, fell in love at twenty-four with Bill Barrett, a good-looking, affable detective, fourteen years her senior. There was one fly in the ointment: old Mrs. Barret, Bill’s mother, who spent most of her life with her feet on the couch, had begged Bill not to marry until God called her. She was sure her death was imminent and wanted him under her roof when her time came.

Months became years. Everyone loved Bill, but from time to time I could hear Mother urging Agnes to ask him about his intentions. They had been keeping company for twenty-four years when God finally beckoned a Barrett, but it was Bill, not his mother, who died. At ninety-five she was still going strong. Her other son, who’d been smart enough to marry young, shipped her to a nursing home. Guess who visited her regularly? Agnes.

At seven I was given a five-year diary, one of those leather-bound jobs with four lines allotted for each day and a tiny gold key which, of course, locks nothing. The first entry didn’t show much promise. Here it is, in its entirety:

“Nothing much happened today.”

But then th

e pages began to fill, crammed with the day-today happenings on Tenbroeck Avenue among friends and family.

When Mother’s sisters and cousins and courtesy cousins came to visit, the stories would begin around the dining room table, over the teacups.

Nora, remember Cousin Fred showing up for your wedding?…

Mother had sent an invitation to some remote cousins in Pennsylvania, forgetting that Cousin Fred had a lifetime railroad pass. He and his wife showed up on her doorstep the morning of the wedding, their nine-year-old grandson in tow. The lifetime pass included the family. Mother ended up cooking breakfast for them and having the kid running around the house while she and May dressed.

Nora, remember how that fellow you were seeing invited Agnes to the formal dance and Poppa was in a rage? “No man comes into my house and chooses between my daughters,” he said.

I loved the old stories. The boys had no patience for them, but I drank them in with the tea. As long as I didn’t fidget, I was always welcome to stay.

Our next door neighbor, Annie Potters, often joined the group. Charlie, a chubby policeman, was Annie’s second husband. She’d been widowed during the flu epidemic of 1917, when she was twenty years old. That husband, Bill O’Keefe, rested in her memory as “my Bill.” Charlie was “my Charlie.” They married when both were in their late thirties.

“I was so lonesome,” Annie would reminisce. “Every night I’d cry in my bed for my Bill. But nobody wants to hear your troubles, so I always kept a smile on my face. They called me the Merry Widow. Then I met my Charlie.”

Charlie died many years later, at the age of seventy, and two years after that Annie married “my Joe.” When God called him to join his predecessors, Annie began looking around but hadn’t connected by the time she was reunited with her spouses.

A woman with a jutting jaw and dyed red hair, Annie had one of the first permanent waves ever given in the Bronx. Unfortunately, when the heavy metal coils were removed, 60 percent of her hair permanently disappeared with them. Nevertheless, when she looked in the mirror, she saw Helen of Troy and conducted herself accordingly. Annie was the model for my continuing character, Alvirah, the Lottery Winner.

Clark, Mary Higgins 03 - The Cradle Will Fall

Clark, Mary Higgins 03 - The Cradle Will Fall Moonlight Becomes You

Moonlight Becomes You No Place Like Home

No Place Like Home I've Got My Eyes on You

I've Got My Eyes on You I've Got You Under My Skin

I've Got You Under My Skin The Lottery Winner

The Lottery Winner As Time Goes By

As Time Goes By Nighttime Is My Time

Nighttime Is My Time Where Are the Children?

Where Are the Children? The Lost Years

The Lost Years Two Little Girls in Blue

Two Little Girls in Blue Mount Vernon Love Story: A Novel of George and Martha Washington

Mount Vernon Love Story: A Novel of George and Martha Washington All by Myself, Alone

All by Myself, Alone The Melody Lingers On

The Melody Lingers On Just Take My Heart

Just Take My Heart The Second Time Around

The Second Time Around A Cry in the Night

A Cry in the Night Deck the Halls

Deck the Halls We'll Meet Again

We'll Meet Again Before I Say Goodbye

Before I Say Goodbye Piece of My Heart

Piece of My Heart My Gal Sunday

My Gal Sunday Weep No More, My Lady

Weep No More, My Lady Daddy's Little Girl

Daddy's Little Girl The Cradle Will Fall

The Cradle Will Fall Manhattan Mayhem: New Crime Stories From Mystery Writers of America

Manhattan Mayhem: New Crime Stories From Mystery Writers of America Where Are You Now?

Where Are You Now? Loves Music, Loves to Dance

Loves Music, Loves to Dance While My Pretty One Sleeps

While My Pretty One Sleeps Pretend You Don't See Her

Pretend You Don't See Her I'll Be Seeing You

I'll Be Seeing You Let Me Call You Sweetheart

Let Me Call You Sweetheart Remember Me

Remember Me Silent Night

Silent Night Kitchen Privileges

Kitchen Privileges All Around the Town

All Around the Town Death Wears a Beauty Mask and Other Stories

Death Wears a Beauty Mask and Other Stories I'll Walk Alone

I'll Walk Alone The Shadow of Your Smile

The Shadow of Your Smile Kiss the Girls and Make Them Cry

Kiss the Girls and Make Them Cry Manhattan Mayhem

Manhattan Mayhem Deck the Halls (Holiday Classics)

Deck the Halls (Holiday Classics) The Cinderella Murder

The Cinderella Murder All Dressed in White

All Dressed in White You Don't Own Me

You Don't Own Me The Christmas Thief

The Christmas Thief Before I Say Good-Bye

Before I Say Good-Bye Dashing Through the Snow

Dashing Through the Snow The Sleeping Beauty Killer

The Sleeping Beauty Killer Mount Vernon Love Story

Mount Vernon Love Story Santa Cruise

Santa Cruise I 've Heard That Song Before

I 've Heard That Song Before