- Home

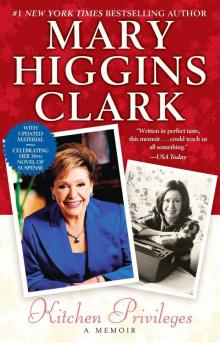

- Mary Higgins Clark

Kitchen Privileges Page 13

Kitchen Privileges Read online

Page 13

Like Lady Bird Johnson, Martha was never called by her given name. When she was little, her father had decreed that Martha was much too formidable a name for such a tiny girl and nicknamed her Patsy. George called her “My dearest Patsy.” She went through the British lines to join him in Boston. She spent the winter in Valley Forge with him.

I wrote a number of scripts about George and Martha Washington, and as I did, an idea began to form in my head. I missed the printed word. I enjoyed writing the radio programs, but they vanished after they’d been aired. On the other hand, I could pick up a magazine that was eight or nine years old and still see my story in print. I wanted to be in print again.

My agent, Pat Myrer, had been urging me to write a novel. “There’s no market for short stories,” she reminded me.

I started thinking about writing a novel about George Washington, one in which the facts and events would be historically accurate, one that would be written from his viewpoint. The seed began to grow. But when would I find the time to do it? There was only one answer: I’d have to get up at five o’clock and work until quarter of seven, when I got the kids up for school.

The first few mornings of the new routine were tough. When the alarm went off, my inclination was to slap my finger on it and close my eyes. But it wasn’t that hard to get used to rising early. And once I was at the kitchen table with the typewriter in place and a cup of coffee at my elbow, it was sheer bliss to be able to work, knowing that the phone wasn’t going to ring, that one of the children wouldn’t need something immediately.

I started to outline the book. I made a couple of flying trips to Mount Vernon. I immersed myself in nonfiction books about G.W. I began the first chapter. I bumped into Pat Myrer on Park Avenue. “Write,” she urged me.

“I’m writing a novel,” I said happily.

“Marvelous. What about?”

“George Washington.”

Seeing Pat’s stunned expression, I forged ahead, gushing about the great love story I would tell about George and Martha.

Pat interrupted me. “Love story between those two? Mary, with those wooden teeth, the only thing George ever gave Martha was splinters.”

But it was an itch I had to scratch. I had to write that book. I knew I was on my way to becoming a novelist.

Twelve

I had flown with Pan Am for a year, but my buddy, Joan Murchison, with whom I’d left Remington Rand to become a stewardess, stayed with the airline for seven years. Then she married a marvelous British war hero, Col. Richard Broad, whom she’d met on one of her trips. When Carol was born, she brought him to visit me in St. Vincent’s Hospital. They made a gorgeous couple. She was petite and blond; Richard was tall and elegant. He’d been an aide to King George VI. When World War II broke out, he was captured and held in a prisoner of war camp in Spain. Sentenced to be shot, he managed to escape with seven of his men. For the next year, they worked their way through occupied France until they finally managed to get back to England. One winter had been spent in the attic of a convent. His group became known as “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

When Joan brought him back to the hospital a second time, I said, “Murch, for the love of heaven, that poor man has better things to do with his time in New York than twiddle his thumbs on a maternity floor.”

She smiled. “Mary, he’s special.”

Richard was indeed special. At that time he was director of a diamond company and was living in Johannesburg. That’s where he and Joan were married. She got back to the States several times a year to visit her mother in Illinois and always spent a few days in New York to catch up with her close friends.

A couple of months after I started working fulltime, I met her at the airport, and we drove into Manhattan. We stopped at a store where she needed to pick up something she had ordered. I waited in the car. When she came back a few minutes later, I was asleep. That was the moment when I realized I needed some household help. I was simply exhausted.

Mother was nearly seventy-eight. She suffered from arthritis, and it was getting harder and harder for her to get around. The kids were starting dinner before I got home, but on several occasions, a neighbor who was a volunteer fireman had to come running over with his fire extinguisher to put out a fire in the oven. Somehow the concept of not putting chops an inch from the flame never did register with my little chefs. We needed help.

One of Tavistock’s out-of-town clients heard that I was fishing around for a live-in housekeeper and called me. He had a friend in her late fifties who wanted to live in the New York area, and she’d worked as a housekeeper. Was I interested? Sight unseen, I took her on. Her name was Peg, and she turned out to be a nice person and a good cook. Also, the driving problem with getting the kids back and forth to activities was solved.

Our arrangement was that she would work from Monday till Friday. The downside was that even though she had the weekend off, she seldom took advantage of it. She stayed around the house on weekends, neither fish nor fowl, helping occasionally, but not really working. And when she did pitch in, she’d take on a slightly martyred expression. Even though we had moved to a larger house in town the year before Warren died, the place wasn’t very roomy. I longed for Peg to disappear on Friday evening and return Monday morning. I wanted time to be alone with my family.

Then out of the blue, I’d sometimes find a note taped to the refrigerator, telling me she’d decided to take a couple of days off. It took a while before it dawned on me that when Peg disappeared, the client who had suggested her to me was in town. I wondered if there was anything going on. I was uncomfortable with the idea of her discussing my household with a client.

Another problem was that I learned that while the kids were in school, Peg was parking my unmistakable bright yellow, nine-passenger station wagon outside the local bar, where she was moonlighting by playing piano for the afternoon drinkers. I hoped that the people in our little town didn’t think that I was the one who had parked it there.

In a lot of ways she was a big help, but when, after a year and a half, she said that she thought it was time to move on, I didn’t shed any tears. She interviewed for and was offered a job as cook working for David Sarnoff, the powerful media giant. His cook had gone to work for Jackie Kennedy Onassis. I told my friends that I was only two kitchens away from Jackie, but ultimately Peg wisely decided that she’d be biting off more than she could chew to be responsible for preparing gourmet dinner parties for up to twelve people.

Instead she moved to California with the family of a television personality. She wrote to tell me that she had become best friends with Florence Aadland, who had written that great first line, “I don’t care what anyone says. My baby was a virgin when she met Errol Flynn.”

G.R. had decided that I’d make a good salesman for the Gordon R. Tavistock radio programming plan. Since that task could earn me a commission on any shows I sold, I was happy to give it a whirl. My only selling experience had been brief and came during my Remington Rand years: I’d had a Saturday job at Lord & Taylor selling coats. The pay had been five dollars a day, but the real perk was the 30 percent employee discount. I loved clothes, and that was a good way to acquire a wardrobe. I’d keep an eye on a dress or suit that I wanted, sure that at some point it would be reduced, then track it until the final reduction and buy it with my 30 percent discount.

I quickly learned that there was a big difference between selling winter coats and getting the advertising executives to sign up for a minimum of fifteen thousand dollars for radio programming. I needed all my Dale Carnegie “win friends and influence people” know-how to get up the nerve to phone an account executive and persuade him to give me an appointment. But I started to fill my appointment book.

My first sale seemed to be an easy one. I had an appointment at J. Walter Thompson, one of the world’s leading advertising agencies. It was also the one for which I had a tender feeling—it was the agency that had hired my son Dave to do the Peanuts commercials for Ford

’s Falcon station wagon, in which he’d been the voice of Linus for four years.

The account executive I saw there couldn’t have been more charming. The kind of publicity I was offering sounded great. He’d be delighted to have his product on radio. Come back with a contract.

Flushed with success, I returned to the office and announced I had made my first sale. “Great!” “Terrific!” “Wonderful!” Then someone asked me what product the agency wanted to publicize.

“Preparation H.”

The smiles faded. I was told that there was no way a highly personal product like Preparation H could be mentioned on the airways. “No wonder the account executive jumped through hoops when he thought he could get a whole series publicizing his product’s soothing qualities,” I was told. “He’d have been promoted on the spot if he could put that one over.” In other words, I not only didn’t have the sale, but I ended up looking like an idiot for even proposing the possibility of one.

Now, when I hear the advertisements for the most intimate products on radio or see them on television, I realize what a quaintly innocent world we lived in less than four decades ago, when the fact that you might suffer from hemorrhoids could not be mentioned on the air. It’s progress of a sort, I guess.

But I did succeed in opening an account with the Nestlé Company. This time the product was chocolate chip cookies, and no one, but no one, had any objection to talking about them anywhere, anytime.

The program was called The Wonderful World of Food. Betsy Palmer was the celebrity hostess. That began my friendship with Betsy that has endured all these years. She’s a great gal, a wonderful narrator, and a terrific actress. The success of that series led to four more with Nestlé.

In the frequent absences of Tavistock, Frank Reeves ran the office. More than that, he was the true heart and soul of the business. He was the kind of person who could sell ice to Eskimos and knew how to make lifelong friends of clients. He kept programs on the air long after anyone else would have lost them. When I went to work for Tavistock, Frank’s wife, Happy, was an invalid. I admired the way that he went straight home after work, taking the train to Long Island. He had a host of friends and constantly received invitations to dinners and parties, but his answer was always the same: “Can’t make it. I have to get home to Happy.”

Not realizing that she was violently allergic to penicillin, Happy had been given a penicillin injection that brought on a stroke. Then she had a second stroke in 1965, the same week that Warren’s brother Allan died. After that, totally bedridden, she lived only another two years.

In addition to being a good husband and boss, Frank was the one responsible for introducing me to Cape Cod. A native of Boston, he had spent all his summers on the Cape. The summer after losing his wife, he rented a house in the town of Dennis and invited five of us from the office to spend a weekend there.

For some reason I’d always been intrigued with Cape Cod. When I was growing up, the women’s magazines had stories about the people who summered on the Cape and whose husbands took the train up for weekends. I considered them an exalted lot and wondered how it would be to live in the place where the Pilgrims first lived when they came over on the Mayflower. The five of us from the office flew up on a Friday in July. Incredibly, it only cost sixteen dollars for the flight. Today the same trip—in what I suspect may be the same plane—costs well over two hundred dollars, one way.

The minute I got off the plane, I felt as though I’d come home. I had the most extraordinary sensation of being in a place that I knew intimately. I don’t believe in reincarnation, but I do wonder sometimes if it isn’t possible that we inherit memory. If we can look exactly like someone who lived hundreds of years ago, if we inherit that person’s particular gift or talent, his or her allergies, isn’t it possible that we can also inherit some awareness that comes from a memory base? I don’t think there are many people who haven’t at some time, some place had a sense of déjà vu: This is familiar but I don’t know why.

Anyhow, that was the response I felt when I got off the plane in Hyannis in July 1968. Déjà vu. Familiarity. Returning home. I’ve never lost that feeling whenever I go there.

I’ve been summering at the Cape ever since. A month after that first visit, I returned to the Cape with the four younger kids. Marilyn had a summer job and wanted to stay home with my mother. I had a number of friends in the Dennis area, so I rented two cabins in a motel unit on Route 6A in East Dennis, where I unwittingly succeeded in terrifying two elderly residents who were luckless enough to be staying in the cabin adjacent to one of ours.

The cabins were small. Carol had a girlfriend, Beth, with her. I stayed in one of the cabins with them and at night sent Patty to sleep with the boys in their unit. They were situated up an incline and a little to the left. The arrangement was that I’d give the boys a few minutes to change for bed, then Patty would join them.

We’d been out for dinner and miniature golf, so it was nearly eleven o’clock when we got back to the motel. The walls were paper thin, so I cautioned Carol and Beth to keep the television down to a whisper. I took Patty, bundled in her pajamas and robe and holding her tattered security blanket, outside. Warrie waved to us from the boys’ cabin, and Patty started up the incline. I watched until she joined Warrie, and he closed the door, then I turned back and realized that the television was blasting. I flung open the door of the cabin, cried, “Are you two trying to wake up the dead?” and rushed over to the television to turn it off.

Then I turned around. What I had not realized was that in watching Pat go up the incline, I had been moving to the right. I was now standing in the cabin next to ours. Staring at me from the pullout bed was an elderly couple, their eyes large with terror, their mouths open. I swear even their teeth, soaking in glasses on either side of the bed, began chattering.

“I’m sorry…I’m so sorry…” Frantically I tried to turn on the television and tune it to the program they’d been watching, but I only succeeded in getting a snow-filled screen and screeching static. With a final mumbled apology, I rushed out of the cabin and went next door where I belonged. Carol and Beth had heard everything through the thin walls and were collapsed in fits of giggling.

The next morning at 6:00 A.M the car in front of the next cabin pulled out. The elderly couple had fled. I hope they came back. I would hate to think that I had driven them from Cape Cod forever.

Thirteen

It had been nearly three years since Warren’s death, but Patty was still stealing into my room at night and then slipping away early in the morning so the big kids wouldn’t think she was a baby. That was why when June bought a dog for her kids and Pat asked if we could get one too. I thought it would be a good idea. Growing up, Johnny and I had always been allergic to most animals, but poodles don’t shed, and I knew I wouldn’t have a problem with one of them.

I was working on my book about George Washington, and we lived in Washington Township. That was how our miniature poodle came to be named Sir George the First of Washington Township. “Georgy Porgy, puddin’ and pie, kissed the girls and made them cry.” That old nursery rhyme inspired us to call our newcomer Porgy. We got him when he was only a few weeks old, and he slept in a shoebox next to Patty’s bed. After his arrival, she no longer made nocturnal visits to my room. While I was very pleased that the addition of Porgy to the household brought some comfort to the kids, especially Patty, he occasionally caused a crisis.

One evening when I arrived home, Patty frantically told me that Porgy had just run out the back door and taken off. I immediately got in the car and began to drive slowly through my darkened neighborhood.

A couple of tense hours later, I spotted him trotting merrily down the block and stopped the car.

“Get in,” I snarled.

Obediently, he hopped in beside me.

All the way home, I ranted at him about his escapade. He followed me into the house, and in the brightness of the kitchen, I realized to my horror that the dog was

not Porgy. I was a dognapper and pictured myself behind bars.

I rushed him back into the car and raced the several blocks to where I had found him. As I shoved him out of the car, I heard a worried voice yelling, “Charley, Charley…” His tail wagging, he bounded away.

A few minutes after I got home, a happy bark from outside the kitchen door announced Porgy’s triumphant return. We later learned that he had returned from a hot date with a lady poodle who had moved in around the corner.

My mother was turning eighty. In the last years, her friends had been celebrating their fiftieth wedding anniversaries. She, of course, had been widowed for some twenty-seven years. I decided that since she couldn’t have an anniversary bash, I was going to throw her an eightieth birthday party. At first I considered making it a surprise, but then I decided that planning is half the fun. I told her what I had in mind, overcame her objections that it would cost too much, and suggested that she start making out a list of the people she wanted to invite.

My mother, Nora, on her eightieth birthday.

She had suffered from arthritis ever since she was twenty. It was indicative of her whole approach to life that she contracted it dancing barefoot in the snow in Central Park when she was nineteen. As she aged, it spread to her knees and legs, her feet and hands, and finally to her back. Her feet were affected the worst, and she literally walked to heaven on those painful appendages, so swollen and sore that she could hardly endure her weight on them. She probably would have been confined to a wheelchair, were it not for the fact that her need to do for other people was so great that she kept pushing herself, forcing activity on those aching joints, willing them to function.

Clark, Mary Higgins 03 - The Cradle Will Fall

Clark, Mary Higgins 03 - The Cradle Will Fall Moonlight Becomes You

Moonlight Becomes You No Place Like Home

No Place Like Home I've Got My Eyes on You

I've Got My Eyes on You I've Got You Under My Skin

I've Got You Under My Skin The Lottery Winner

The Lottery Winner As Time Goes By

As Time Goes By Nighttime Is My Time

Nighttime Is My Time Where Are the Children?

Where Are the Children? The Lost Years

The Lost Years Two Little Girls in Blue

Two Little Girls in Blue Mount Vernon Love Story: A Novel of George and Martha Washington

Mount Vernon Love Story: A Novel of George and Martha Washington All by Myself, Alone

All by Myself, Alone The Melody Lingers On

The Melody Lingers On Just Take My Heart

Just Take My Heart The Second Time Around

The Second Time Around A Cry in the Night

A Cry in the Night Deck the Halls

Deck the Halls We'll Meet Again

We'll Meet Again Before I Say Goodbye

Before I Say Goodbye Piece of My Heart

Piece of My Heart My Gal Sunday

My Gal Sunday Weep No More, My Lady

Weep No More, My Lady Daddy's Little Girl

Daddy's Little Girl The Cradle Will Fall

The Cradle Will Fall Manhattan Mayhem: New Crime Stories From Mystery Writers of America

Manhattan Mayhem: New Crime Stories From Mystery Writers of America Where Are You Now?

Where Are You Now? Loves Music, Loves to Dance

Loves Music, Loves to Dance While My Pretty One Sleeps

While My Pretty One Sleeps Pretend You Don't See Her

Pretend You Don't See Her I'll Be Seeing You

I'll Be Seeing You Let Me Call You Sweetheart

Let Me Call You Sweetheart Remember Me

Remember Me Silent Night

Silent Night Kitchen Privileges

Kitchen Privileges All Around the Town

All Around the Town Death Wears a Beauty Mask and Other Stories

Death Wears a Beauty Mask and Other Stories I'll Walk Alone

I'll Walk Alone The Shadow of Your Smile

The Shadow of Your Smile Kiss the Girls and Make Them Cry

Kiss the Girls and Make Them Cry Manhattan Mayhem

Manhattan Mayhem Deck the Halls (Holiday Classics)

Deck the Halls (Holiday Classics) The Cinderella Murder

The Cinderella Murder All Dressed in White

All Dressed in White You Don't Own Me

You Don't Own Me The Christmas Thief

The Christmas Thief Before I Say Good-Bye

Before I Say Good-Bye Dashing Through the Snow

Dashing Through the Snow The Sleeping Beauty Killer

The Sleeping Beauty Killer Mount Vernon Love Story

Mount Vernon Love Story Santa Cruise

Santa Cruise I 've Heard That Song Before

I 've Heard That Song Before